OUT-TAKES by Photographer Jack McConnell

TIPS for photographing in cold, snowy weather:

In winter I look forward to going out with my camera at dawn just after fresh snow has fallen, or at the tail end of a storm when snow is sticky and clings to trees. It seems like everything is a picture, and I’m a giddy kid in a candy store.

Winter scenes are monochromatic, letting you really concentrate on composition. Shooting photographs is a Zen-like process, for a photograph represents the smallest instant of time. Nothing that comes before it or after it matters at all. Anything just beyond the picture frame may as well be a million miles away. It’s a constant reminder to experience life in the moment. If you go out open-minded, with an empty hand, you can almost always find a photograph.

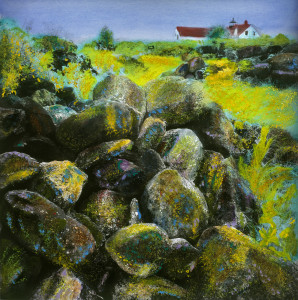

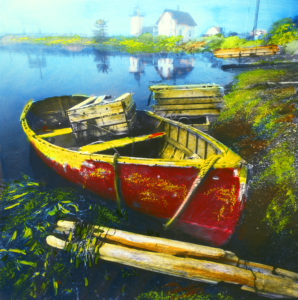

Going wide. It’s just me, I guess, the way I choose to see, but I find the most pleasing images are made with either a wide-angle or telephoto lens, and as I approach a scene I start to pick out the elements that will work best together. I like to emphasize foregrounds and increase the visual perspective between foreground and background, or to compress the perspective of a scene with a telephoto lens.

Timing is everything …the U-turn. Often, when a shot doesn’t work out the way I want it to, I try to return to the scene in different light. But it almost never works out. The weather, the light, my mood is different. Someone has plowed the roadside between visits. Highway workers have set out safety cones. Rarely do I get a second, better chance. So I try everything I can to get my shot the first time round.

It’s the little things in life that trip you up, like exposure: The first problem people have when shooting in snow conditions is getting the exposure right. Their tendency is to under-expose the scene, forgetting that the in-camera meter wants to see everything as 18% medium gray. Depending on what percentage of the scene is white snow, you have to open up 1 stop, or even more.

Approaching the scene: Be careful not to contaminate your scene with footprints as you make your decision about where to set up to shoot. If you’re in slippery conditions, consider using ice creepers over your shoes to give you a better grip. These are available in sports shops like Maine Sports.

Keep hands warm by using a pair of winter golf gloves, which will protect your hands from direct contact with cold metal. They are slightly sticky feeling on the surface, so your equipment won’t slip out of your grasp. Put hand warmers in your pockets and put your gloved hands in there at every opportunity, and you’ll do just fine. Bare hands get too cold, mittens and winter driving gloves are bulky and awkward to use. Gloves with finger tips removed are useful, but hands can become very cold. Put foot warmers in your boots, outside of your socks. Always wear a hat, because you lose a lot of heat through your head. Dress in moisture-wicking layers as you are likely to have a few minutes of exertions, followed by a period of waiting around for conditions to change.

Use a tripod: 95% of the time I take the time to set up a tripod to insure sharpness. A carbon-fiber tripod is expensive, but doesn’t conduct cold as much as aluminum does. I use a wood tripod, but if you’re using aluminum, try wrapping plumbing pipe insulation around the legs to reduce hand contact with cold metal.

Condensation: The worst thing you can do in extreme cold conditions is to accidentally breathe on your viewfinder or lens as you’re leaning over your camera to set your f-stops and shutter speeds. This can cause frost, and even permanent damage. Likewise, if you’ve put your camera under your jacket to protect from falling snow, you can cause condensation when you bring it back out into the cold air. At the end of the day, I put my camera back into the camera bag, close it up, and let it warm up slowly for several hours inside the house, before I take the camera out. Otherwise put your gear in large plastic bags while still out in the cold before bringing into the warm house, so condensation forms on the bags rather than your camera.

Composition: I don’t particularly follow the historical “rules of composition”. If I do it in a composition, it’s generally by accident. I try to shoot a lot. The more I shoot the better I get, even after all these years. I like close-ups and details. Hard to find, but worth the effort. I look for contrasts—big vs. small, light vs. dark, warm colors vs. cool, hard against soft. Barns, fences, trees, a group of people provide contrast to the snow.